“. . . and there is nothing new under the sun.” (Ecclesiastes 1:9)

We are often told that we are living in unprecedented times, but the burning issues of today are similar to those of the U.S. in the 1920s: deep cultural, social, and political divisions, including the urban-rural divide; high and rising wealth inequality; resurgent anti-immigration policies and white supremacy; rising Christian nationalism; ascendant isolationism; and the demonization of scientists and expertise in general.

Statue of Darrow outside the

Rhea County Courthouse

in Dayton, TN (Full image)

(Credit: David M. Lodge)

One of the defining events of that period, the Scopes “Monkey” Trial, in the county courthouse of Dayton, Tennessee, concluded 100 years ago this week. As a university-based evolutionary biologist and Christian who grew up within 50 miles of Dayton, and whose parents lived in the house that once belonged to the trial’s judge, I see some strikingly contemporary lessons in this anniversary, particularly around the question of who has the power to choose faculty and curricula in schools and universities.

The Scopes Trial 101

The trial determined whether high school teacher John Scopes had violated a recently passed Tennessee state law that banned the teaching of “any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals.”

No one, including Scopes, denied that he had taught from a biology textbook that included evolution, but he pled not guilty because both sides wanted a trial. Prosecuting attorney William Jennings Bryan and defense attorney Clarence Darrow, both well-known national public figures, saw an opportunity to make the trial about the influence of the majority’s Christian faith on school curricula vs. the First Amendment separation of church and state, and the rights to religious liberty and free speech.

As chronicled in Brenda Wineapple’s 2024 book, “Keeping the Faith: God, Democracy, and the Trial that Riveted a Nation,” Bryan was the son of a Virginia-born Southern sympathizer who became an Illinois state senator and judge. Bryan himself was a supporter of the Lost Cause, states’ rights, popular sovereignty, and majority rule. To many of the public, he was the “Great Commoner,” a powerful Fundamentalist Christian orator, proponent of Prohibition, and three-time presidential candidate for the Democratic Party.

Darrow, the son of abolitionist parents, was committed to individual rights, and had become famous for successfully defending unpopular, hard-to-defend defendants, including alleged murderers and spies, in nationally prominent cases.

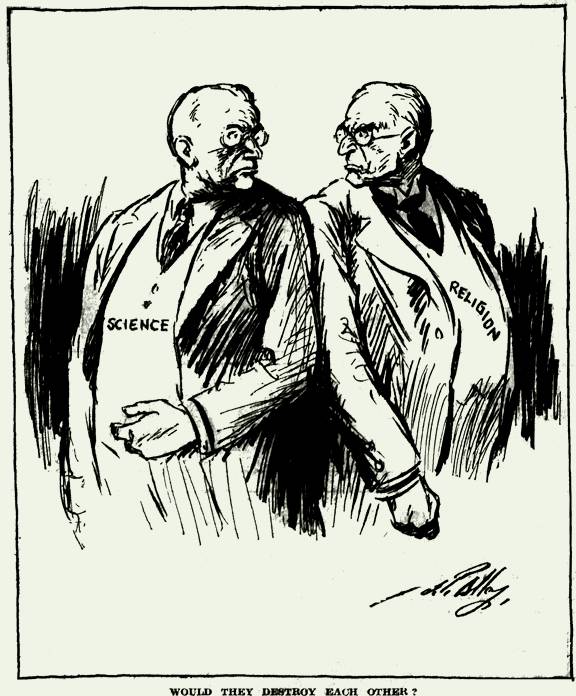

“WOULD THEY DESTROY EACH

OTHER?” Political cartoon in

Commercial Appeal

(Memphis, TN, 6/6/1925)

Equal disdain shown between

science and religion. (Full image)

(Credit: Darwin Online)

In Wineapple’s telling, the trial was for Darrow about who controlled how Americans could be educated. For Bryan, it was about protecting the public’s Christian faith and practice from evolution, which Bryan correctly saw was being used (illogically) to support Social Darwinism, which in turn justified laissez-faire capitalism and opposition to any policies to make American society fairer for the common person.

Scopes was declared guilty – a legal victory for the prosecution but a cultural and political victory for the defense. Bryan had consented to being cross-examined by Darrow, who humiliated Bryan by getting him to admit that he didn’t actually believe in a six-day Creation, which Bryan’s most ardent supporters saw as central to their faith.

Both Bryan and Darrow had asked the jury to convict, with Darrow hoping to elevate the fight with appeals up to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Tennessee Supreme Court, however, threw out the conviction on a technicality. It wasn’t until 30 years after the Scopes Trial that the U.S. Supreme Court supported the teaching of evolution with rulings in Epperson v. Arkansas (1968) and Edwards v. Aguillard (1987) that public school curricula could not favor a particular religious view.

Where We Are Today

The polarization characterizing the 1920s remains alive and well today. Indeed, in his 2022 book “The Right,” Matthew Continetti argues that it is impossible to understand Donald Trump’s politics without looking to the religious populism and America First movements of the early 19th century embodied by Bryan.

Bryan and Trump are similar in their opposition to the elitism and condescension too often emanating from universities then and now. However, Trump’s political rhetoric and policies often align with the Social Darwinism so despised by Bryan.

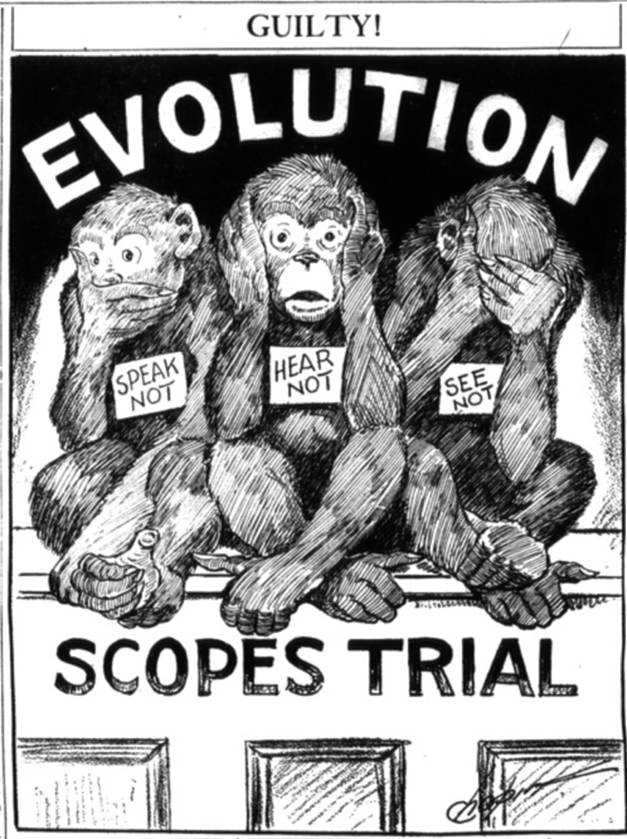

“GUILTY! EVOLUTION: SPEAK

NOT, HEAR NOT, SEE NOT –

SCOPES TRIAL” Political cartoon

in San Francisco Examiner

(6/22/1925) (Full image)

(Darwin Online)

For many Christians, the Scopes Trial is seen as a victory of godless elitism over Christian faith and virtue. For many scientists, including many of my fellow biologists, it is viewed as a simple victory of science over ignorance. Both views lack the nuance necessary to bridge the mutual comprehension that divides us.

A 2025 study shows that religiously affiliated people’s skepticism toward science is rooted in their concern about the morality of scientists, which, no doubt, is part of the legacy of the Scopes Trial. That is an invitation to my fellow scientists and me to embrace our commitment to science – not the mishmash of science and values called scientism – and seek to better understand the legitimacy of the concerns of religious people in and outside of universities.

The Trump administration’s ongoing punishment of universities provides an opportunity for those of us who inhabit them to redouble our commitment to welcoming colleagues of diverse views into civil discourse, while defending the university’s prerogatives in hiring and firing faculty. Recognizing how science and its discoveries can be misunderstood or misused – as by the Social Darwinists and eugenicists of the 20th century or the New Atheists of the 21st century – should humble those of us in science as we make future decisions on who to hire as colleagues and what we teach in the classroom.

Header photo: On the Scopes trial’s seventh day, proceedings were moved outdoors because of excessive heat.

William Jennings Bryan (seated, left) is being questioned by Clarence Darrow. (source: Wikipedia)

Learn more about David M. Lodge