Since the start of the Industrial Revolution, humanity has been conducting an inadvertent global geoengineering experiment: emitting carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. The experiment has been a side effect of all the benefits received from the use of fossil fuel-derived energy for heating, cooling, moving around, growing food, making things, and generally increasing human welfare. For several decades, though, it has been well known that climate change and its many increasingly high costs have accompanied the benefits of burning fossil fuels.

Over the 40+ years of my research career, proposed ways to reduce the costs of climate change have widened. First, the entire focus was on mitigation — reducing emissions of greenhouse gases to eventually reverse climate change. When it became clear that the nations of the world were not doing that nearly fast enough, even the most diehard environmentalists began to acknowledge that a second kind of response would be required: adaptation.

Failing to stop climate change means that we humans must adapt by changing our behavior and systems to reduce our vulnerability. Adaptation includes smarter zoning for residential and commercial development, new construction standards, breeding drought resistant crops, and protecting shorelines with gray (e.g., seawalls) or green (e.g., saltmarshes, mangroves) infrastructure. In the US and elsewhere, a great deal of investment in both mitigation and adaptation continues, but even such combined efforts are not yet commensurate with the pace and magnitude of climate change impacts.

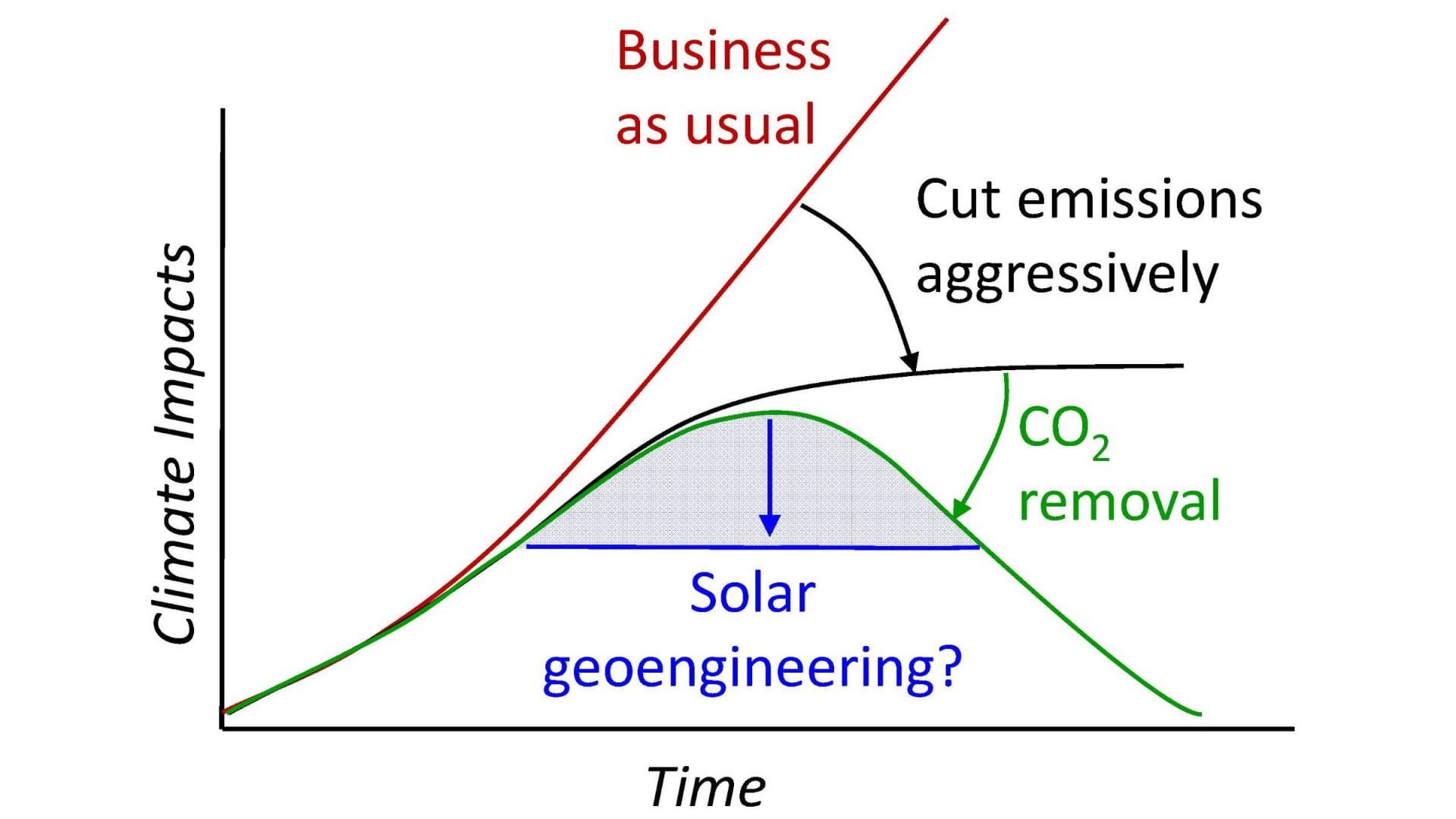

Hence a third kind of response, geoengineering, has recently entered mainstream discussions. Most of the interest lies in solar radiation management, which is reflecting sunlight back into space, reducing Earth’s energy imbalance directly. While this would in no way affect the underlying problem (the rising CO2 concentrations), it could provide a brief respite from the growing negative effects produced by the warming. Therefore, those who think of geoengineering as part of the solution speak of needing an all-of-the-above approach.

Learning From Unintentional Experiments

What do we know about how an intentional solar geoengineering experiment might reduce the impacts of the long-term addition of greenhouse gases into the planet’s atmosphere

Intermittently during the 250+ years since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, we or the planet itself has conducted other, sometimes global-scale, geoengineering experiments that have reversed some impacts of climate change.

In 1991, when Mount Pinatubo erupted, a massive plume including tons of sulfur dioxide was launched from the Philippines as high as 15 miles into the atmosphere — into the stratosphere. During the next two years, sulfate aerosols that resulted from the eruption reflected sunlight sufficiently to cool the earth about 1oF and change weather patterns for the subsequent two years. The effects declined as the sulfate particles fell out of the atmosphere.

After 2020, when global regulations requiring lower sulfur fuel for ships came into effect, the reduction in cloud-seeding sulfate emissions reduced the occurrence and reflectivity of “ship tracks” — the bright white, very reflective linear clouds that form around ships’ emissions. Such tracks were fleeting and limited to the ocean, of course, and much more abundant in the northern hemisphere. Nevertheless, according to a 2024 study, reducing air pollution from ships inadvertently increased slightly the rate of global warming. Or to put it another way, it reduced one mechanism of global cooling. This side effect was anticipated, but was quietly ignored by policymakers.

Debating the Role of Solar Geoengineering

Considering what we’ve learned from these previous unintentional geoengineering experiments, the idea that an intentional injection of sulfate aerosols into the stratosphere could cool the planet is neither far-fetched nor beyond the reach of research. In a keynote panel last month, Cornell experts Natalie Mahowald, Doug MacMartin, and Dan Visioni explained what is known, what is unknown, and what further model-based research could reveal. They also addressed some criticisms of the idea, which is as controversial as adaptation was 25 years ago.

One example of opposition to geoengineering is a recent letter calling for “an International Non-use Agreement on Solar Geoengineering,” which garnered signatures from many leading scientists. The primary goal of the statement is to prevent solar geoengineering from becoming a viable policy option alongside mitigation and adaptation. In support of that goal, it calls for prohibiting technology-oriented R&D that would enable deployment, as well as outdoor scientific experiments, while begrudgingly allowing for at least some idealized research to continue.

There are several reasons for the caution, if not the outright opposition, reflected in the letter.

First, even if deployed with the desired effect of cooling the earth, solar geoengineering will not lessen all the impacts of greenhouse gases. For example, ocean acidification caused by increasing atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide would be unreduced by solar geoengineering. Thus solar geoengineering should never be seen as a substitute for mitigation and adaptation. At best it would be a temporary stopgap measure to buy time as mitigation and adaptation ramp up.

Second, deployment should never be considered unless uncertainties are reduced about the impacts and the geographic and demographic distribution of those impacts. For example, which country’s agricultural production would be helped or harmed, and by how much?

Third, there is no multilateral governance mechanism to oversee any decision to deploy solar geoengineering or to manage the consequences. With multilateral organizations under attack, it is hard to imagine one emerging anytime soon. This is especially important because the technological and financial barriers to deploying solar geoengineering are not high. Many individuals and governments have the means to deploy solar geoengineering, and some may have the motivation in coming years. Stardust Solutions, a private, for-profit geoengineering start-up, has recently raised $60M in a new round of funding for its proprietary approach. The for-profit motive and small-scale experiments proposed or executed by others in Sweden, Mexico, and the U.S. have reduced societal trust in research on this topic.

An Informed Path Forward

Cornell Atkinson has supported modeling and governance work on geoengineering over the last decade, and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. We believe that learning more about the potential benefits and costs is prudent in case deployment is ever seriously considered. All Cornell researchers involved hope that mitigation and adaptation efforts will increase and obviate any contemplation of deployment. However, using climate models to learn more about geoengineering’s potential benefits and costs is better than remaining willfully ignorant. As pointed out in a letter in response to the letter arguing for non-use, there is also risk in not learning about geoengineering.

The Cornell-based research led by Doug MacMartin and Dan Visioni includes collaborators of diverse expertise using global climate models to identify likely trade-offs of different deployment strategies; identify uncertainties by degree of importance and the magnitude of uncertainty; and identify likely impacts and how they differ across different deployment designs. All these research strands are conducted with transparency, open access to data, and linked to global efforts for equitable policy and governance efforts like the Degrees Initiative.

At Cornell Atkinson, we will continue to take unconventional approaches to explore fully how to leverage research toward positive impact for the people and the planet. One aspect of doing that is to define for policymakers the knowns and the unknowns of solar geoengineering.

David M. Lodge is the Francis J. DiSalvo Director of the Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability