The headlines are alarming: East Coast braces for surge of invasive flying spiders. Invasive crabs have taken over New England. Invasive pest with deadly venom spreads across the US.

We are inundated with bad news about nonindigenous invasive species, including lionfish, feral hogs, Japanese knotweed, spotted lanternflies, murder hornets, Asian stinging ants, Asian longhorned ticks, flying Joro spiders, European green crabs, golden oyster mushrooms, and golden mussels. Nonindigenous invasive species are one of the top causes of biodiversity loss and other unwanted change to nature – on par with climate change, land use, overharvesting, and pollution. Recent estimates of the financial cost in the U.S. over the last 50 years range from $900 billion to over $1.22 trillion, increasing by tenfold over that time.

In addition, nonindigenous parasites and pathogens increasingly threaten the health of humans, livestock, and wildlife. For example, the nonindigenous virus SARS-CoV2 (the virus that causes COVID) killed at least 19,000 people in the U.S. in the last year, and H5N1 and H5N5 (the viruses currently causing outbreaks of bird flu) caused at least 71 human cases and two deaths in the U.S. since 2024. Burmese pythons and related constrictors continue to kill lots of wildlife and a person about every other year in the U.S.

At the U.S. science-policy interface, reducing the harm from such species has been a goal of established policy with strong bipartisan support during my four decades of work on this issue. Preventing species from arriving (vs. reacting after they are here) has long been recognized as the most cost-effective management strategy for nonindigenous invasive species. However, neither public nor private investment in prevention has been at a level commensurate with the damage. In fact, total investment has been small. For example, in 2020 the U.S. Department of the Interior spent only $143 million responding to nonindigenous invasive species. Only 3% of expenditure was devoted to prevention, where the bang for the buck is greatest.

If prevention makes so much sense, why is it underinvested?

I’ll offer five reasons for the underinvestment in prevention and some associated recommendations.

First, the public often misunderstands the scope of the problem, in part because messaging from some environmental groups seems to demonize all nonindigenous species. Many nonindigenous species – including cows and soybeans – bring far more benefit than harm. U.S. policy, however, focuses on preventing the arrival in the U.S. only of those species that are likely to cause more harm than good to humans, other creatures, and/or infrastructure that humans care about.

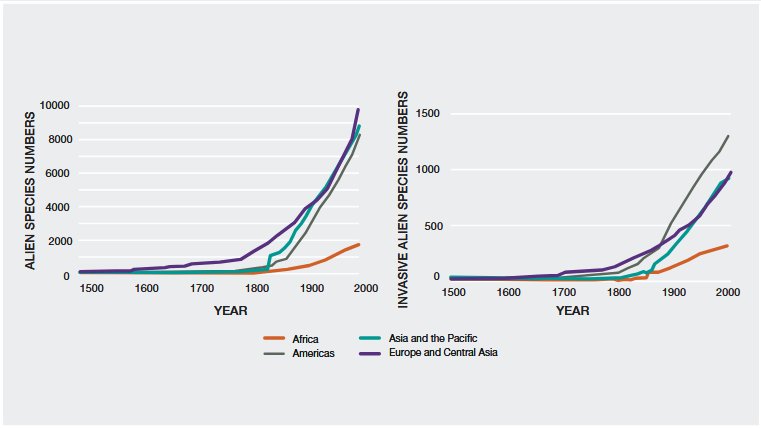

A comprehensive list of nonindigenous invasive species that are established in the U.S., if such a list existed, would be very long. We know that over 8,000 nonindigenous (or “alien”) species exist in the U.S. (left side of figure below). If advocacy groups and the media focused on the roughly 13% of those species that are likely to cause more harm than good (right side of figure below), the public would be better informed, and the country would be better protected.

Second, the staggering number and diversity of species that arrive in the U.S. can make the problem seem insurmountable. This is reinforced by the media, which typically focuses on one species presented as a fascinating horror story of strange biological features and impacts. This obscures the fact that prevention efforts often don’t need to focus initially on the species. Rather, a policy focus on the two categories of pathways that bring nonindigenous species to our shores is far more effective and efficient: transportation-related pathways, including commercial shipping; and commerce in living organisms, including the horticulture and pet industries.

Third, for both types of pathways, the damages from invasives species are an economic externality. The damages are spread across society as an invisible invasive species tax of about $1,000-$10,000 for each of the 130 million U.S. households annually, based on the damage estimates cited above. Therefore, while the damages are not felt acutely by anyone, the benefits are concentrated in the pathway industries, which are motivated to oppose policy that would put the damages on their balance sheets. Without effective policy and implementation to internalize those costs, the public good continues to suffer.

Fourth, local and state policymakers recognize that species do not respect political jurisdictions, and therefore polices below the federal level will be much less effective. Compared with air pollution from smokestacks or water pollution from effluent pipes, for which dilution is often the solution, nonindigenous invasive species reproduce and spread. Instead of going away with time and distance, the problem grows exponentially in time and geography. This is why the costs of nonindigenous invasive species are accelerating so rapidly over time. This is a classic weakest link problem, which only U.S. federal policies can overcome.

Fifth, the definition of success for prevention is that nothing bad happens. It’s hard to build and maintain public and policy support for regular expenditures on something for which the results are invisible. Prevention for the common good requires government leadership.

Despite these five hurdles, the constant drumbeat of arrivals of new species would have an even faster tempo if we hadn’t made a lot of progress in preventing and managing such species in recent decades. In my next blog post, I’ll share two such policy successes, and emphasize the importance of investing in tools and technologies to help inform and enforce prevention policies.

Header photo: The wreck of the Iona ship in the Red Sea offshore from Yanbu, Saudi Arabia offers the setting for a beautiful lionfish (iStock).

David M. Lodge is the Francis J. DiSalvo Director of the Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability